From a Historical Perspective to Future Policy Considerations

On March 12, 2020, Gov. Tony Evers issued Executive Order #72 to declare “a Health Emergency in Response to the COVID-19 Coronavirus.”[1] This order would direct all state agencies to respond to this public health crisis including the Department of Health Services (DHS) “as the lead agency,” the Adjutant General was “authoriz[ed]…to activate the Wisconsin National Guard as necessary and appropriate to assist in the State’s response to the public health emergency,” and the Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection (DATCP) was “[d]irected…to enforce prohibitions against price gauging during an emergency.”1

Legislative efforts to cut red tape prior to COVID-19 are also aiding in emergency response efforts. In 2015, Gov. Walker signed a bill relating to the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, which has increased access to licensed health care workers from other states to practice in Wisconsin. In 2019, legislators removed more barriers to healthcare by improving access to telehealth, which is currently being used in efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

As Wisconsin and the rest of the world work tirelessly to address COVID-19, there is an importance in understanding the various aspects of emergency preparedness that have been pursued over the years at the state and local levels by a wide variety of pivotal stakeholders. Gov. Tommy Thompson, an important figure in Wisconsin’s history, also has particular insight into our country’s response during a pandemic due to his role as the Secretary of U.S. Department of Health & Human Services from 2001-2005.[2] Gov. Thompson also served as Governor of Wisconsin from 1987-2001.2

During Gov. Thompson’s tenure as Secretary, he led national efforts to combat public health crises such as the SARS outbreak,2 which is also a “viral respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus.”[3] In an interview with WisconsinEye, Gov. Thompson talked about how it was during his tenure as the Secretary of U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that he was tasked with efforts to “rebuild our public health system” because America “didn’t have the surge capacities…or the kind of equipment necessary…” to address public health emergencies.2 During his tenure, he said that at the federal and state level,

“We were able to rebuild surge capacities… across the states. We had plans put in place that people knew what to do…People were schooled in emergencies…what would we do if we had a catastrophe? How would we take care of people that needed treatment?”2

It is important to understand efforts at the state and local level to increase emergency preparedness over the years. However, it is also crucial that policy leaders reflect on this information to guide additional efforts on how to address future public health crises and other emergencies that may threaten our citizens.

Examples of Wisconsin’s State Agency Preparedness

DHS Related

As noted by Executive Order #72, DHS became “the lead agency to respond to [this] public health emergency” and this agency was directed to “take all necessary and appropriate measures to prevent and respond to incidents of COVID-19 in the State.”1 Since this Executive Order, DHS has compiled such information as: community resources, impacts and program responses, and “how DHS and other public and private partners are helping reduce the spread of COVID-19.”[4]

In order to respond to COVID-19, the State Emergency Operations Center (EOC) has brought together key public-private partnerships to address this public health emergency. These efforts have brought together DHS “doctors, nurses, and public health professions, other staff from across Wisconsin state government [that are] working alongside health care system partners, leaders from Epic Systems, the Wisconsin Emergency Management, and the National Guard.”[5] Today, the Wisconsin State Emergency Operations Center is at its highest level, a “Level 1,” which,

“…is a full activation of the State EOC with WEM, DMA, DHS (Dept. of Health Services), DNR, DOT Highways, State Patrol, DATCP, and DOC having representatives in the EOC. Other state agencies and volunteer organizations will be requested to send representatives to the EOC depending on the nature of the event and the need for additional support to local jurisdictions.”[6]

Together, these State EOC teams “are creating and implementing plans on important topics like essential supplies, contact tracing, and lab capacity, in an ever-changing situation.”5 This work covers such crucial areas as:

- “Testing” and “testing infrastructure”5

- “Contract Tracing”5

- “Health care capacity” to assess “current capacity and…to address any projected needs to ensure they have the space, supplies, and staff to provide the vital services needed to address the pandemic.”5

- “Isolation Facilities” “in Milwaukee and Dane counties.”5

- Assess and acquire “[p]ersonal protective equipment (PPE) and essential supplies” in order to provide “medical and public safety professionals… with the equipment they need to help keep our communities safe and healthy.”5

- “Essential worker child care” to better provide child care resources to essential workers.5

- Data collection “to inform…modeling.”5

While DHS leads the COVID-19 response and the teams within the State EOC continue these collaborative efforts with their wide array of partners, it is important to recognize additional emergency preparedness measures that have been established in Wisconsin.

During Gov. Scott McCallum’s time in office, in 2002, DHS created the Wisconsin Healthcare Emergency Preparedness Program (WHEPP).[7] This program was developed due to a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services grant.7 As explained by the Wisconsin Hospital Association (WHA) approximately 15 years later, the purpose of this program was to:

“…support the emergency preparedness efforts of hospitals and other health care partners by providing equipment, supplies, resources, training and infrastructure. Over the last 15 years, WHEPP has provided millions of dollars to Wisconsin hospitals and health care systems for emergency preparedness.”7

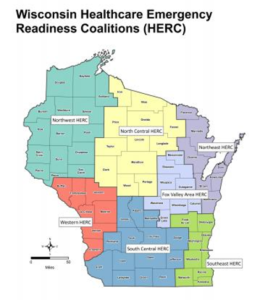

In 2014, under Gov. Scott Walker’s administration, Wisconsin went on to create the healthcare emergency readiness coalition (HERC).[8] As noted by DHS, there are seven regional coalitions that cover the state and:

“A healthcare emergency readiness coalition is a group of healthcare organizations, public safety and public health partners that join forces for the common goal of making their communities safer, healthier, and more resilient. The coalitions support communities before, during, and after disasters and other health-related crises.”8

The HERC regions include:

![]()

- Northeast Region

- Northwest Region

- North Central Region

- Fox Valley Region

- Southeast Region

- Western Region

- South Central Region

These Coalitions and its members pursue projects that improve regional emergency preparedness through collaborative relationships, planning efforts, and compiling necessary resources.[9] During an emergency, these Coalitions take part in coordinated responses and other mitigation efforts,[10] while providing needed resources to their community.[11]

These are examples of collaborations that have been led by DHS and are designed to confront emergencies that impact Wisconsin residents including COVID-19. These coalitions, response teams, and numerous other partnerships have been created over several administrations, but they are all doing the crucial work to respond, mitigate, and help our local communities recover from emergencies.10

DMA Related

As stated on the Department of Military Affairs’ (DMA) website, this agency “provides essential, effective, and responsive military and emergency management capability for the citizens of our state and nation.”[12] This agency encompasses the “Joint Force Headquarters-Wisconsin, Wisaconsin Army and Air National Guard, Wisconsin Division of Emergency Management, and the Office of Emergency Communications, there is the Wisconsin Emergency Management (WEM).”12 WEM is located in Madison with “six regional offices that provide local support.”[13] This agency, is “charged with coordinating the state’s planning, preparedness, mitigation, response and recovery efforts for natural and man-caused disasters,”[14] and,

“WEM creates and maintains the Wisconsin Emergency Response Plan (WERP) to manage multi-agency state response to large-scale emergencies that exceed local response capacity. The WERP provides integration between local jurisdictions and state and federal agencies and is the mechanism for requesting federal disaster assistance.”[15]

![]() The most recent WERP available on WEM’s website was revised in November of 2017.[16] This 948-page plan includes the following notes on its purpose,

The most recent WERP available on WEM’s website was revised in November of 2017.[16] This 948-page plan includes the following notes on its purpose,

“As a home rule state, Wisconsin recognizes that the safety and well-being of every resident of every jurisdiction in the state are the responsibility of the senior elected officials at the lowest level of government affected by an emergency. It is the premise of this plan that all levels of government share the responsibility for working together in preventing, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from the effects of an emergency or disaster incident.”16

On April 20, 2020, Dr. Darrell L. Williams, WEM Administrator, talked about the agency’s efforts to confront COVID-19.[17] In a video, Dr. Williams highlighted WEM’s collaborative efforts with “state agencies, county emergency managers, and our public-private partners [who] have been working with us 24 hours a day to develop plans of action and to implement best practices to keep Wisconsinites safe.”17 The agency continues its work to:

- “make progress towards efforts that will save lives in the future”17

- “[coordinate] with our hospitals and medical professionals to stand up isolation centers and alternate care sites”17

- “[improve] our communication plans and efforts with our counties and with our tribes”17

- “[work] with volunteer organizations and other stakeholders to address a myriad of issues in the wake of COVID-19”17

Another example of the DMA’s efforts to address COVID-19 include the work of Wisconsin’s National Guard service members that help our local communities across the state and serve in several different capacities. They remind us that:

“Members of the Wisconsin National Guard live in every county in Wisconsin and stand ready to serve at home…As Soldiers don protective gear or practice safety precautions while training to potentially interact with individuals who may have been exposed to COVID-19, it’s important for the people of Wisconsin to remember who is underneath the suit, behind the mask, and in the uniform. Neighbors who love the Green Bay Packers, know 32 degrees is not cold, live for a Friday fish fry and who are serving to make their home a safer place…”[18]

Along with the work of DHS, the work being done within DMA shows the current commitment to confronting COVID-19 and the agency’s continual efforts to plan on how to respond and mitigate emergencies that threaten Wisconsin’s public health and safety. As, Dr. Williams explained, collaborative efforts are working around the clock “to keep Wisconsinites safe” and “address a myriad of issues in the wake of COVID-19.”17

Policy Initiatives

On March 27, 2020, Gov. Evers and DHS Secretary-designee, Andrea Palm, signed Emergency Order #16, which “Related to Certain Health Care Providers and the Department of Safety and Professional Services Credentialing.”[19] This Emergency Order was part of the COVID-19 response because “the continued spread of COVID- 19 demands that we have the help of as many skilled health care providers as possible.”19 As a result, items relating to such issues as: “Interstate Reciprocity” and “Telemedicine” were ordered.19

In the case of “Interstate Reciprocity,” the Emergency Order removed barriers from health care providers from other states, so that they could provide assistance and help address where there are health care provider shortages on our front lines of this crisis.19 The Order did include such caveats as health care providers have “a valid and current license issued by another state” and these health care providers “may practice under that license and within the scope of that license in Wisconsin.”19

Interstate Medical Licensure Compact

The idea of addressing health care provider shortages by removing licensure barriers can also be seen through previous legislative efforts regarding the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. In December of 2015, Gov. Walker signed 2015 Assembly Bill (AB) 253 into law, 2015 Wisconsin Act 116,[20] and this legislation “enter[ed] Wisconsin into the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact.”[21] The Compact is “a multi-state agreement that creates a streamlined process for physicians to become licensed in multiple states.”21

During the public hearing on this legislation, WHA testified that this legislation would “…remove redundant red-tape in the medical licensure process and thus increase access to care in Wisconsin communities…”[22] In 2019, WHA further highlighted the importance of this Compact when the legislation to reauthorize the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact was proposed in the Wisconsin State Legislature.[23] This legislation, 2019 Senate Bill (SB) 74, was proposed by a group of bipartisan legislators led by Sen. Patrick Testin (R- Stevens Point) and Rep. Nancy VanderMeer (R-Tomah), and became 2019 Wisconsin Act 49 when it was signed into law.[24] During his testimony on the legislation, Sen. Testin explained the benefits of eliminating redundant aspects of this bureaucratic licensing process,

“Since April 2017, nearly 400 physicians residing in other states have used the Compact process to become licensed and serve patients in Wisconsin…Wisconsin health care organizations have also utilized the Compact to reduce staff time spent on credentialing physicians and used the work done by other states, rather than duplicate government processes.”[25]

Telehealth

“Telemedicine” also is not a new concept in Wisconsin but remains a topic of continual discussion within the legislature. As explained by WHA, telehealth is:

“…the delivery of health care services remotely by means of telecommunications technology, can help to improve access to health care services by allowing patients to receive care locally in their communities by connecting to existing providers in other locations. Common examples of telehealth include virtual office visits, telestroke services, remote patient monitoring, and remote evaluation of patient information.”[26]

In 2019, legislation was introduced by a bipartisan group of legislators that were led by Sen. Dale Kooyenga (R-Brookfield), Minority Leader Janet Bewley (D-Mason), Rep. Amy Loudenbeck (R-Clinton) and Rep. Debra Kolste (D-Janesville) in order to improve access to telehealth services.[27] This legislation was introduced because, as WHA notes, there were “real-world barriers associated with Wisconsin’s current Medicaid telehealth policies.”[28] This legislation was signed into law at the end of last year and became 2019 Wisconsin Act 56.27 However, as the bill authors noted in their testimony,

“Wisconsin health care providers are increasingly utilizing telehealth to improve access to essential care. Unfortunately, state laws and policies are not keeping pace with advances in technology and care delivery innovations and are preventing telehealth from reaching its true potential.”[29]

WHA notes that, “One of the top three issues facing hospital and health system leadership continues to be a healthcare workforce to sustain Wisconsin’s nation-leading healthcare system.”[30] As the legislature evaluates potential proposals on how to address this problem that faces communities all across the state, it is important to reflect on these examples of policy initiatives that removed unnecessary bureaucratic processes and helped increase access to health care provider services.

Efforts to Address COVID-19 by Wisconsin Companies

In addition to public-private partnerships and other collaborative efforts that are responding to the threat of COVID-19, there are companies that have shifted their production to provide the supplies and support needed to those on the front lines of this public health emergency. The following companies below are just examples of headlines that have highlighted companies in Wisconsin that are taking part in this effort:

- BizTimes: “GE Healthcare to produce ventilators ‘around the clock’”

- Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: “Exact Sciences in Madison ready to process 20,000 coronavirus tests per week, expanding Wisconsin’s testing capacity”

- WPR: “Promega Helping Supply Materials For COVID-19 Tests”

- BizTimes: “Foxconn donates 100,000 masks to state of Wisconsin”

- TMJ4: “Medline Industries transforms Hartland facility to help produce more hand sanitizer”

- BizTimes: “Jockey donating PPE, including 250,000 isolation gowns, for coronavirus fight”

Conclusion

It is important to recognize the work by all levels of government to pursue emergency preparedness and the collaborative efforts of public-private partnerships that strengthen Wisconsin’s response to emergencies. Those involved in Wisconsin’s emergency preparedness routinely pursue planning and training projects in order to provide the best response to a wide range of potential emergencies. During our darkest moments, they work tirelessly including through their efforts on the front lines of an emergency.

Everyone on the front lines of this public health emergency and every emergency deserve our sincerest gratitude for the work they do every day. It is also important to recognize the collaboration that will also go into recovering from COVID-19, preparing for other emergencies that may threaten Wisconsin, making sure policies are enacted that will further strengthen Wisconsin’s emergency preparedness, and continuing to pursue innovative legislative solutions that eliminate unnecessary red tape and improve access to health care.

[1] https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/WIGOV/2020/03/12/file_attachments/1399035/EO072-DeclaringHealthEmergencyCOVID-19.pdf

[2] https://wiseye.org/2020/03/17/covid-19-tommy-thompson/

[3] https://www.cdc.gov/sars/index.html

[4] https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/index.htm

[5] https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/seoc.htm

[6] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/wem/home/current-status

[7] https://www.wha.org/WisconsinHospitalAssociation/media/WHA-Reports/WHA-EmergencyPrepBrochure-2-7-2018.pdf

[8] https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/preparedness/healthcare/index.htm

[9] http://www.wiherc.org/projects.phtml

[11] http://www.wiherc.org/resources.phtml

[13] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/wem/home/about

[14] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/wem

[15] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/wem/preparedness/response-plan

[16] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/divisions/wem/preparedness/2017_WERP(Full37M).pdf

[17] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/wemnews/2020wemnews/ready200420

[18] https://dma.wi.gov/DMA/news/2020news/20046

[19] https://evers.wi.gov/Documents/COVID19/EMO16-DSPSCredentialingHealthCareProviders.pdf

[20] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2015/proposals/ab253

[21] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2015/related/lcactmemo/act116.pdf

[22] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/hearing_testimony_and_materials/2015/ab253/ab0253_2015_08_18.pdf

[23] https://www.wha.org/WisconsinHospitalAssociation/media/WHACommon/CommentLetters/2019TestimonyAssemblyHealthWHA7-10.pdf

[24] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2019/proposals/sb74

[25] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/hearing_testimony_and_materials/2019/sb74/sb0074_2019_03_14.pdf

[26] https://www.wha.org/telehealth

[27] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2019/proposals/sb380

[28] https://www.wha.org/WisconsinHospitalAssociation/media/WHACommon/CommentLetters/2019WHATestimony-Supports-AB410-Assembly-Medicaid-Reform-Committee09-24.pdf

[29] https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/hearing_testimony_and_materials/2019/sb380/sb0380_2019_10_09.pdf